|

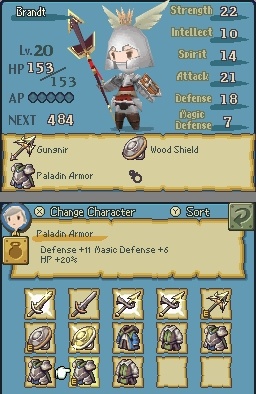

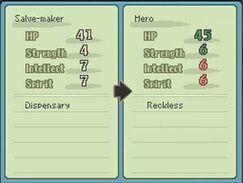

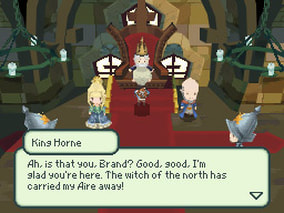

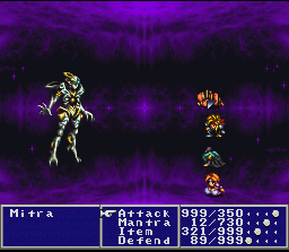

Random Encounters is a blog series celebrating the achievements and unique aspects of Japanese Role-Playing Games with a look at their development history, play experience and cultural impact. Blogs may be updated in the future as my feelings on the game change or to correct factual inaccuracies that escaped my attention. Final Fantasy: The 4 Heroes of Light is an interesting place for this blog series to start. It makes sense for a topic as it is the most recent JRPG I have completed, but it is a fairly obscure game that has been overshadowed by its much more successful successor Bravely Default and a game that I still have some mixed feelings about in terms of execution. Nevertheless, its experiments with some core mechanical assumptions of the genre and that of Final Fantasy series in particular are worth highlighting. Enough waffling, let's dive in! Development History Final Fantasy: The 4 Heroes of Light (henceforth called 4 Heroes) was a role-playing game developed by Matrix Software and published by Square Enix in October 29, 2009 for the Nintendo DS. Matrix Software is a Tokyo based studio best known for the Alundra series (a dreamdiving action RPG series, will definitely do a blog for it later) and its collaborations with Square, Enix (and later the merged company) and Chunsoft. 4 Heroes was marketed as a deliberate throwback to the older Final Fantasy games with its key distinguishing points being its picture book aesthetic (that ageless Windwaker look), streamlined Job system (using Crowns) and a wireless co-op multiplayer mode allowing up to 4 players to play together. Key figures on the development team were the director Takashi Tokita (lead designer on Final Fantasy IV, director on Parasite Eve and Chrono Trigger), the producer Tomoya Asano (who would go on to be a Producer for the future Bravely series), and concept artist Akihiko Yoshida (best known for art on Matsuno games and now known for Nier: Automata). Game scenario was written by Asano and Tokita in collaboration with Izuki Kogyoku who had worked on the very unique Fragile Dreams: Farewell Ruins of the Moon for the Wii. Music for the game was composed by Noashi Mizuta best known for work on Final Fantasy XI at the time and now Final Fantasy XIV. Much of the development team carried over from doing Final Fantasy III (2006) and Final Fantasy IV (2007) remakes for the Nintendo DS. The game came out in Japan as 光の4戦士 -ファイナルファンタジー外伝 (Hikari no Yon Senshi: Fainaru Fantajī Gaiden). The "Gaiden" tagline establises that it as a spin-off to the main Final Fantasy series. This would be the second time this tagline was used after 1991's 聖剣伝説 ~ファイナルファンタジー外伝~ (Seiken Densetsu ~Fainaru Fantajī Gaiden~) which we know as Final Fantasy Adventure (first game in the Mana series). There was some speculation that due to the number '4' on its website that this game would be the next numbered game in the SaGa series, but this was corrected by the game's full announcement. Mechanics Overview 4 Heroes' claim to be a throwback to NES/SNES era JRPGs is not an empty one as its core gameplay loop is very much the same: go to a new location, talk to NPCs to push forward the plot, go to a dungeon area, fight the Boss, get a reward and repeat. However, it is in the details that 4 Heroes makes some of its boldest design decisions. The player moves their party around an on-screen map using the D-Pad or Stylus. On the Overworld, party members will be shown following the lead character (there is a cute detail in that the rate at which they follow varies, I think it might be tied to what Equipment they are wearing or their Agility values). Every X number of steps the player will have a random encounter with a group of enemies corresponding to that region of the Overworld. Later in the game, the player acquires a Ship to cross oceans and a Dragon to fly over everything to improve their travel of the Overworld. The Overworld goes through a Day/Night cycle as well as localized weather effects. It should be noted that Towns/Dungeons have a 3D presence on the map. Players can spot the floating magic city of Spelvia early on by seeing its shadow across the moon at Night which is a lovely little detail. For Towns and Dungeons, players can talk to NPCs, buy/sell/store Items/Magic/Gear, rest up at an Inn, or in some locations play Mini-Games. In Towns, the party splits up and the leader can speak with individual members of the party (there are some variant responses depending on who the leader is). There are also narrow crevices in towns which can be accessed once the party acquires the Animal Staff. These secret areas contain either information or later Items/Magic/Gear which lets the player sequence break a little. Dungeons are similar to Town areas other than the fact like the Overworld the party follows the leader again and there are random encounters every X number of steps taken. Some Dungeons have puzzles that gate progression and others are dark requiring the use of a Torch item to find their way through. A key thing about 4 Heroes' economy is there are two currencies at work: Gold and Gems. Gold works like it does in most RPGs, however, if your party gets wiped you don't lose any Gold. Gems are the far more important resource in the game. There are 8 different kinds of gems which Enemies drop and they can be 1) sold to gain Gold which lets you buy things, 2) used to upgrade Crowns to gain new Abilities, or 3) used to upgrade certain types of Gear to improve stats. Each kind of Gem is worth a different amount and so tougher enemy groups may give sets that are more valuable than weaker ones. If the party gets wiped, you will lose half (rounded down) of one type of Gem This last point is critical as it can either make party wipes toothless or devastating: losing 10 Rubies is not that big a deal (worth 500G) but losing 10 Amethysts (worth 20000G) sets you back a long ways. From my playthrough, it seemed the best thing to do with Gems was not hoard them and use them immediately for the next thing I wanted so that if I wiped (and I did often) it would not be too awful. Most of a player's time in 4 Heroes will be spent either in Battle or in their Inventory. Battles are instanced, turn-based affairs much like NES/SNES JRPGs of old but with a key twist being use of AP. Each party member can have up to 5 AP which can be expended on Abilities that they have set for themselves before the Battle. Three Abilities will always be available: Attack (a regular weapon attack), Boost (defending and gaining 1 AP) and Item (using an Item from your Inventory) will always be there. Other Abilities either come from your Crown (class abilities essentially) or from Spellbooks (they have to set in your Abilities to use them in Battle) in your Inventory. Over the course of the game, you will get more party members and more Ability options and so this simple system can lead to a lot of different combinations. AP values carry over from Battle to Battle, so there is an incentive to end Battles with high AP. As I mentioned previously, targeting is automated so there is a sub-game of getting your party members into the right conditions to use their Abilities on the desired target. Due to turn order being based off Agility (it's there even though they have hidden the stat), it is difficult to predict the order in which actions will happen. This makes healing, buffing and item use particularly difficult at times in Battle where your party members will consistently mess up due to factors outside the player's control. Later in the game, you get accessories that let you control the order of when a party member will execute their actions but by then its too late and you are well frustrated. Enemies on the other hand seem to work independently of this AP system with Bosses taking double or even triple turns to perform their Abilities. Enemies can also be brutal by focusing down a single target and having your party on the back foot for the rest of the battle. I've read that their behavior is governed by an Enmity/Aggro system but outside of the Abilities of the Paladin and Ninja Crowns, it was never clear how the player could control their attention. YOU ALSO CAN'T ESCAPE FROM BATTLES unless you have a member with a Wayfarer Crown with that exact Ability. Inventory plays a big part in 4 Heroes as each party member is restricted to 15 Inventory Slots with each Item taking up 1 Slot. This means that for a full party, the player has only 60 Inventory Slots available. There is a Storage Box that can be accessed in Towns which contains 99 Slots, but even so the restriction of what Items the player brings is a key factor in how long they can crawl through a dungeon and what types of characters they can make. 4 of these Slots will usually be occupied with Gear, so you are now down to 11 Slots and since Spellbooks take up Slots that is even fewer available for miscellaneous Items. For most of the game this restriction won't affect you too much and it's there to encourage players to go back to Town after grinding and sell off/use up old stuff rather than hoard it. There are also two Crowns that focus on Item Use (Salve-Maker and Alchemist) and so it makes sense why this limitation is there. Just prepare to spend a lot of time trading items between party members. Last, but not least, let's talk about Crowns. Crowns are this game's take on the Job System from Final Fantasy III and Final Fantasy V. By wearing a Crown, a party member's stats and weapon proficiency are modified and they get access to a new set of Abilities. In a departure from its predecessors, 4 Heroes does not restrict Gear or Spells based on what Crown they wear leading to many different build combinations. There are 28 Crowns in the game (including Freelancer which means no Crown), most of which are unlocked over the course of the story but some of which are acquired through other means (at endgame). Crowns can be upgraded by matching a set of Gems that is required at each Level. Different Crowns will require different sets of Gems, but generally Level 1 requires 2 different kinds; Level 2 requires 3 different kinds and 1 Amethyst; Level 3 requires 4 different kinds, 2 Amethyst and 1 Diamond. At each Level, it confers a new Ability for the party member that can be used in Battle. Interestingly enough, Abilities that are more powerful versions of earlier ones can be used independently of each other. For example, Black Mage gets "Magic Mojo" Ability at Level 0 and "Spell Power" Ability at Level 1 both of which make your next attack spell do more damage. The player can use "Magic Mojo" then "Spell Power" then a spell and get the benefit of both. There are also Abilities that modify other Abilities such as Salve-Maker's "Dispensary" which gives infinite uses of "Item" or Spell Fencer's "Magic Sword" which changes a member's weapon Element to one of the Spells they have set to their Abilities. Crowns are a great deal streamlined from the Job System which I think makes them more successful. Final Fantasy III's Job System was restrictive in its use of the Capacity System (later Job Adjustment Phase) which locked you into a Job for long periods of time and Final Fantasy V's Job System focused on grinding AP to gain Abilities and then switching back to whichever Job had the best modifiers. By having progression be dependent on Gem collection and allowing instant changes between Crowns, I would argue that this is a much more robust system for the trial-and-error players can engage in to figure out what combinations work best against a certain Boss / Dungeon rather than grind and stick to their preferred solution. Play Experience 4 Heroes' campaign can be said to be structured in two parts: The first part (lasting roughly 10 - 12 hours) has the party come together than split apart and travel across the world before coming together again, then a world changing event occurs leading to the second part (lasting roughly 24 - 48 hours) where the reunited party goes around the World to defeat 7 Bosses in any order before the way to the final Dungeon opens. WARNING: Mild spoilers ahead! The first part of the game begins with the player going on what seems to be a routine RPG mission from the King to rescue a princess from the clutches of a Witch. The party is slowly gathered together over the course of the first dungeon (Witch's Mansion) and ends with a battle against said Witch. Upon defeating the Witch, the party are contacted by a Crystal and get the power of the Crowns to fight against the oncoming darkness. The party returns to their village of Horne to find that it has been cursed and from there split ways. The narrative then cuts back and forth between each party member as their (mis)adventures take them to each of the locations around the world, fight Bosses causing problems in the area and unlock more Crowns as a reward. The party eventually reunites in Spelvia where they must fight against Rolan, the Hero that previously saved the World by sealing demons of Chaos who has since grown cold to the needs of humanity. The party is successful in defeating Rolan but they let loose said demons he was holding back and the world descends into darkness as a result. This part of the game was difficult to play through given that there is very little initially about the combat and the exploration to make it exciting. A lot of the strategy and decision making is taken care of by the automated targeting. Once Crowns get unlocked, things get a little bit more interesting as you get new powers and moves, however at the rate you earn Gems it takes a while before you get any key unlocks (this speeds up dramatically once you get the Merchant Crown). Splitting the party actually makes the game a great deal more difficult as your early game options are few and the game doesn't scale for enemies at different party sizes (there does seem to be some level scaling, but this causes issues later). As a result, you will wipe frequently losing you a lot of Gems in the process. Narrative elements are also a good deal less engaging as the main characters aren't able to play off each other. There are details though if you dig deep enough, such as if you use the Animal Staff on each character they turn into a different animal and the others in your party will comment on how the traits of the animal are reflective of each character (e.g. Yunita turning into a Rabbit and Aire commenting how they shouldn't leave her alone alluding to her feelings of abandonment). The game also doesn't hold your hand too much in terms of guidance (which is good thing later, but a bad thing now) and so you can spend hours bumbling around unable to figure out what trigger you have to pull or where you have to go to get the next part of the plot moving. The second part of the game takes place in a time shifted (dark) world and has the party going back to each of the Towns they visited, defeating the released Demons and gathering the Weapons of Light to confront Chaos. They now have access to a Dragon so the Overworld opens up greatly allowing the player to approach each area in any order of their choosing. The narrative slowly reveals how the problems that the player ran into in the first part of the game came to be and how their intervention can change the outcome. Upon defeating all 7 Demons, the path to the final Dungeon (Star Chamber) will appear and the players can go and confront Chaos for a climactic battle. As bonus content, mysterious Towers in different parts of the world can be opened in the endgame which have procedurally generated floors with rare items and bosses that the player can clear in order to earn the final Crowns. These Towers are filled with tough enemies and have great rewards in terms of EXP, Gems and Items. This part of the game is the main reason to play 4 Heroes. Its sheer confidence in letting the player just bash their heads against the walls until they are able to make a breakthrough is incredible. The experience playing from Level 25 - 60 is great as there is a steady stream of Crown unlocks and new Gear to support it. The Weapons of Light are each pieces of Gear/Spellbooks that have distinctive traits that get the player to build around them in mind. It is a clever way of both powering up the party but also getting the player to exploit some Crown interactions. One key issue though that has persisted throughout the game and especially egregious in this higher level section was that the Gem drops were not varied enough to support Crown upgrades. Since Gems of higher value are given as reward for defeated enemies, you are effectively starved of Gems of lower value unless you grind in a specific region or have a member with a Merchant Crown at all times (which I ended up having to do). This poor distribution of Gems is one of the greatest flaws of the game as these are a resource critical to so many other systems and having the wrong kind just gates you from getting necessary upgrades to keep pace with the game. This could easily be rectified by having an in-game method of trading Gems such that even if the player was losing net worth in the trade, they would still get the combinations they wanted for the purposes of progression. This flaw caused me to spend more time in the game grinding and I believe that caused the endgame to outstay its welcome. All of that being said, Chaos was a satisfying Final Boss battle to end the game on. I was down to my last character (said Merchant who only survived by having an Ability that can spend Gold to negate Damage) and won just by a hair. Impact & Legacy As implied in the introduction, the impact of 4 Heroes was minimal. It sold well enough moving 115,000 units on the week of its release. Critical response was mixed to positive with it holding an average Metacritic score of 71/100. Folks praised its charm in evoking the NES/SNES era of JRPGs while point to its poor signposting, trial-and-error bosses and grinding as negatives. And then it sort of vanished ... Keep in mind, this was near the end of the DS' lifespan and there were already talks of the 3DS. In terms of Square Enix's lineup for that year, the big focus was Final Fantasy XIII which was coming out later in December 17, 2009. The development team would go on to turn their ideas for a 4 Heroes sequel into the successor game Bravely Default: Flying Fairy which was massively successful and has gone on to become its own series. There are a number of callbacks to 4 Heroes in Bravely Default such as the Demons of Chaos appearing as optional Nemesis bosses, a large number of enemy models being uprezzed and included in the game (such as the Orc), the NPCs Adventurer and Fox Companion returning and some rearranged music tracks. I hope this blog encourages you to check out Final Fantasy: The 4 Heroes of Light. It is a game that tries to do a lot of interesting things that belie its (pandering) nostalgic exterior. Not all of these things are successful, but this is the kind of experimentation that I believe needs to be done to create the space for better games in the genre. It is rare that someone looks at a JRPG and says, "Hey, that games' economy is fascinating!". 4 Heroes is a flawed Gem in the lineup of Nintendo DS RPGs, but that makes it a unique entry that is well worth studying. Thank you for reading and I'll catch you next month with a new Random Encounter. This blog was written using information from Wikipedia, Final Fantasy Wiki and a number of other blogs and articles. Images have been sourced from various places through Google Images. A more detailed bibliography will be added here at a later date.

0 Comments

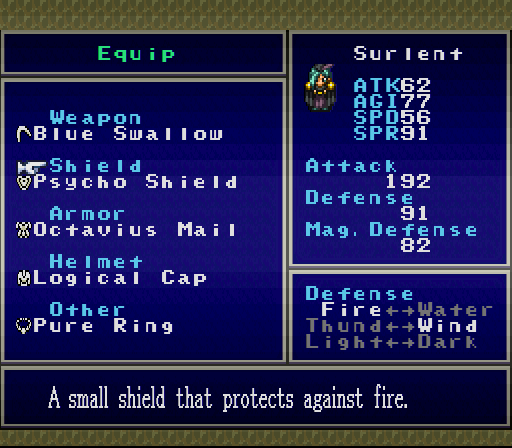

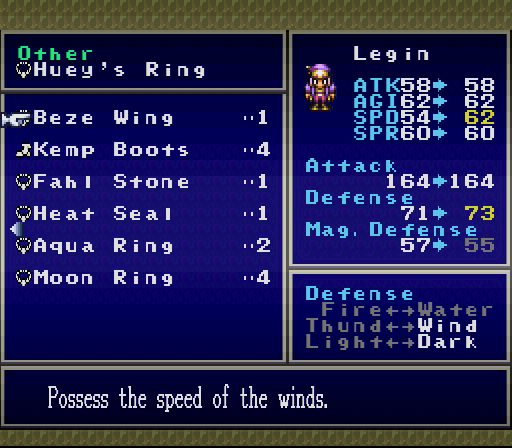

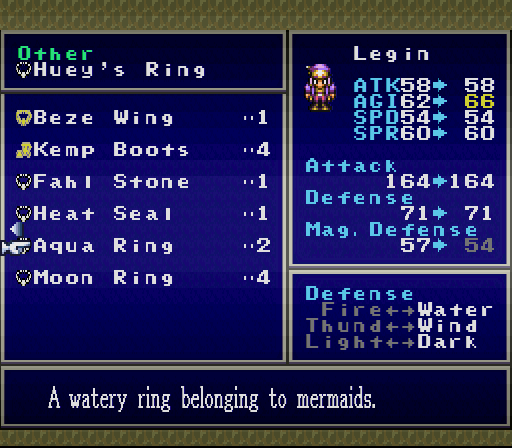

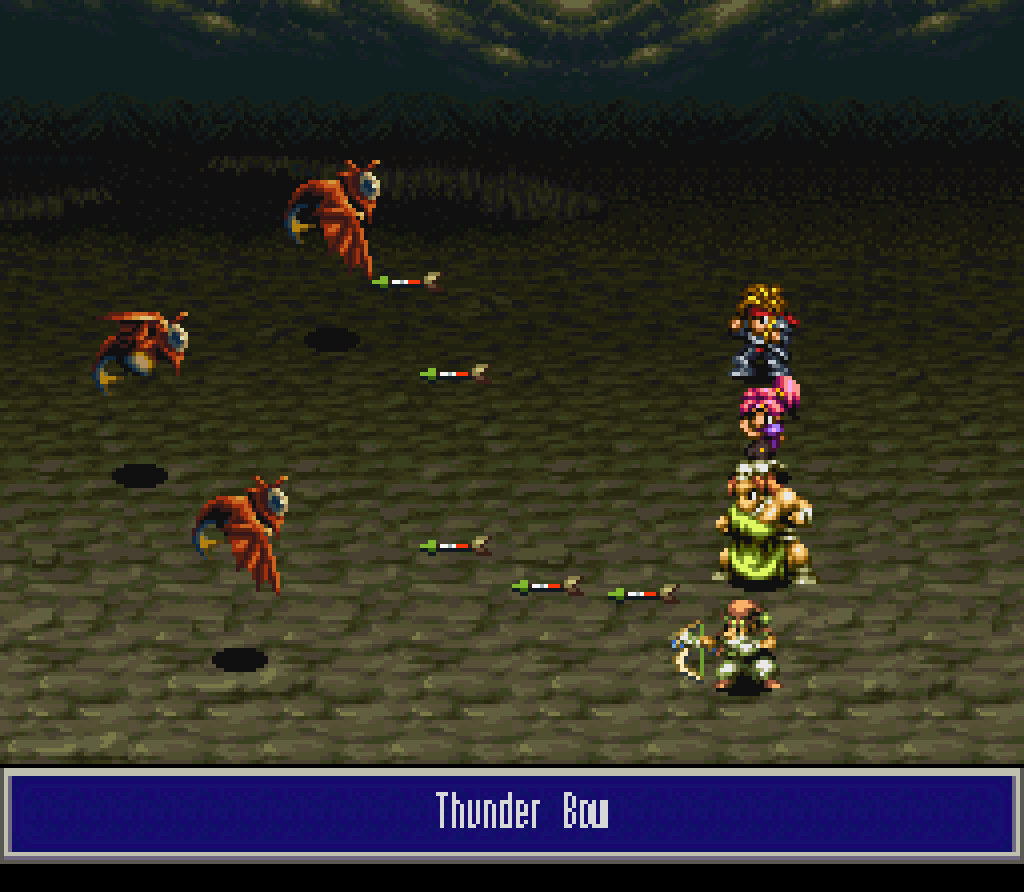

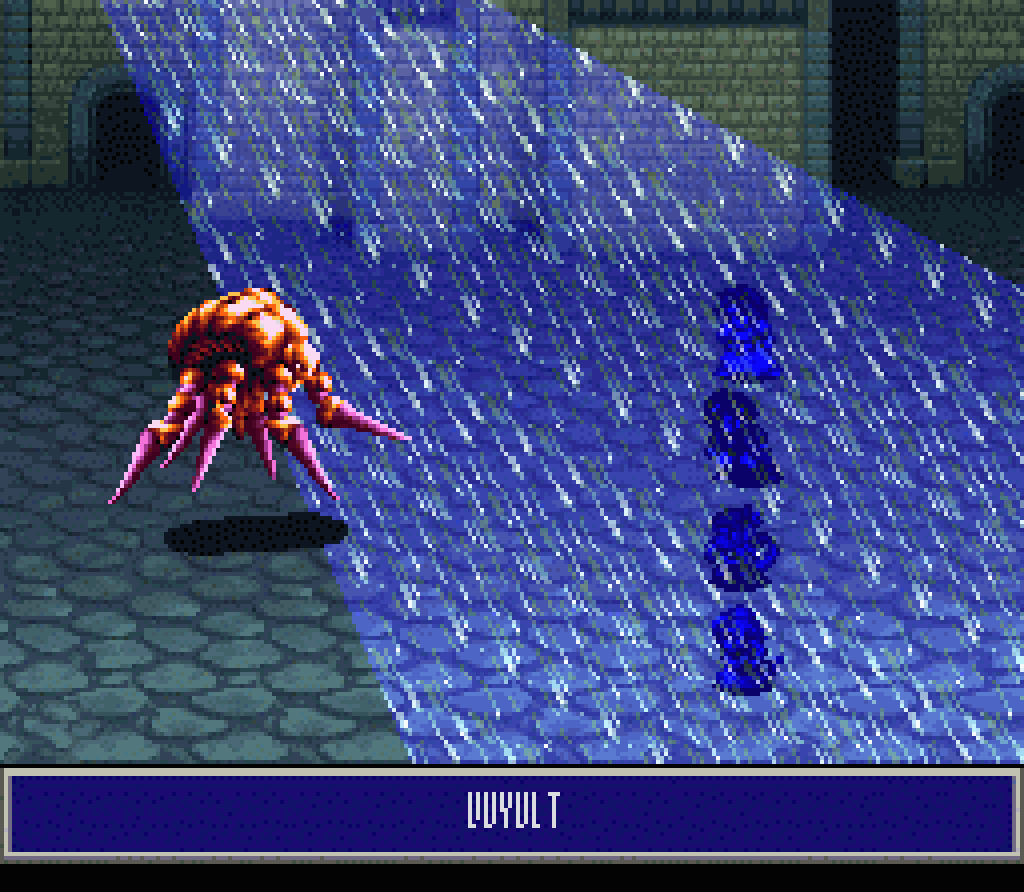

Design Gold is a series of short blogs reflecting on an effective element of game design in a game that I am currently playing and how it works to better the overall play experience. Blogs may be updated in the future as my understanding of how that element works changes. Treasure of the Rudras (Rudra no Hihou) is a 1996 JRPG by Square for the SNES that features a lot of interesting design decisions. Players take on the roles of three heroes (later united by a fourth) each on a quest to stop the end of the world in 15 days. Credited with its design is Akitoshi Kawazu who was also responsible for the design of the early Final Fantasy games and its much more experimental cousin the Romancing SaGa series. The DNA of the latter can be clearly felt in Treasure of the Rudras which has elements of non-linear storytelling and innovative systems. Treasure of the Rudras was never released outside of Japan, however, it can be played via ROM using a fan translation by the group Aeon Genesis (who were also responsible for the translations of Shin Megami Tensei ROMs). Most discussions of the game center around its incredible Mantra system which has the player combining different words and phrases to build spells of different elements, effects, ranges and magnitudes. Even more incredible is the fact that a system that so heavily uses characters of the Japanese language was translated into English in more or less working form. However, this blog will focus on something much more granular: how Elemental Affinity of characters is handled with Equipment. Elemental Affinity is a popular mechanic is a number of JRPGs. There are n Elements that make up damage types. If you use Elements of one kind on an enemy, you get a benefit. If you use Elements of another kind on enemy, you will get punished. You can think of it as a sort of color matching mini-game used to make combat feel less deterministic. Most may be familiar with how the Pokemon series handles it with Type Advantages (e.g. Water beats Fire, Fire beats Grass). It is an intuitive mechanic for most players as it offers an immediate First Order Optimal (FOO) strategy to get the players feeling skillful for their choice in-game. Series in the Final Fantasy mold give this mechanic a bit of a nod to make gameplay for magic users more interesting by conferring a x1.5 - 2.0 damage multiplier if you hit an enemy of the opposite element (its vulnerability/weakness) and a x0.5 - 0.75 damage multiplier if you hit an enemy of the same element (its strength/resistance). The same rules will generally apply to your party making for some variation in Equipment (e.g. Weapons that make your normal attacks of a certain Element or Armor that makes you resistant to an Element). This mechanic is developed upon in the mid-late game where most enemies will nullify or absorb damage from certain elements, making players move onto Non-Elemental Damage spells. At that point, however, things get significantly less interesting as Elemental Affinity is ignored in favor of raw power, and in such games physical attackers generally scale better than magic users so why not just hit the 'Attack' button every turn (a problem worth discussing in another blog). Treasure of the Rudras, while certainly in the Final Fantasy mold, does something interesting with its Elemental Affinity system. As a game with spell casting as a core feature using its Mantra system, the player is told very early on that enemies will have certain resistances and weaknesses so they should try to experiment with a variety of different spells. However, it is possible for both enemies and party members to have multiple resistances and weaknesses. There are six Elements in Treasure of the Rudras that are set in pairs opposite to each other : Fire vs Water, Thunder vs Wind, Light vs Dark. There are two additional elements Void and Earth which are not part of this pairing, working similarly to Non-Elemental Damage in other games. So, if an enemy is using Fire spells and in the Thor Volcano area, the player will probably be able to defeat it easily with a Water spell, being its opposite in the pairing. When it comes to the party members things get more interesting. Let's say to get past an area with a lot of enemies throwing Fire spells, the player was to put on equipment that makes a party member resistant to Fire (e.g. Huey's Ring). By doing this, however, they have now made that party member vulnerable to Water. This can be devastating later in the game where enemies can mix up the Elements they are attacking with and so what was once useful has now become a liability. This applies to all three of the opposite pairings, so a player can make a character resistant to Fire, Wind and Dark but they are now vulnerable to Water, Thunder and Light attacks. The player can choose to not have any resistances (therefore no weaknesses), but they leave themselves open up to the raw power of the Elements which could be fatal if their Spirit attribute (what determines their Magic strength and defense) is low. So, you might be thinking, that's pretty neat but does it warrant an entire Design Gold blog? There are certainly other games that have done Element Affinities in a much more interesting manner (don't fret, we'll get to Shin Megami Tensei and Divinity: Original Sin eventually) since the release of this decades-old game. And you would be right, but I think the implications created by this simple mechanical variation are worth exploring in significant detail. On a single character basis, this makes determining their loadout an interesting puzzle. If the player knows the dominant Element of a dungeon area or boss battle, they could equip them with that same Element to reduce damage taken. However, this is not always simple as Elemental Affinities of various pieces of equipment can cancel each other out. For example, Logical Cap has a Wind Affinity and Thor Ring has a Thunder Affinity. If a character were to equip both, then those Affinities would cancel out leaving the character without a defense in either. By doing this, the mechanic subtly encourages the player towards certain Equipment sets over the course of the game rather than being explicit about what makes up a given set. The player could also opt to go counter the dominant Element being used (e.g. going for Wind when the dungeon has enemies that use Thunder). This is a much riskier setup but could pay off if the character has a high Speed attribute (what determines Turn order) and if the player has a Weapon that attacks in the same Element that they have a resistance to (if the two share Element Affinities, there is a significant damage bonus conferred). For characters that use ranged weapons (such as Legin, pictured above), it is possible for them to attack every enemy at once with Machine Guns/Crossbows and so for most of the game I had him with the counter Element Affinity so that he could go first and mow through mobs of random encounters. Once the player approaches late game, a constant question will come up on whether you equip a newly found piece of Equipment based on its stat benefits vs its Elemental Affinity. Players are rewarded for holding onto old pieces of Equipment because they will frequently run into an area where the highest stated items won't cut it and they need to change Affinities. All in all, there are 25 combinations of Element Affinities for each character so it allows for great flexibility on how players want to equip them. On a party composition basis, this becomes an even more engaging puzzle as you are trying to find the best combination to go through a given area or Boss fight, but also having to balance those needs with what you buy from shops and how you distribute equipment among your party members. While there are some Bosses are of a single Element and only attack with that Element, most of them in the later stages of the game will vary their attacks and use party-wide attacks so it is difficult to plan for every inevitability (though I am certain there are speedrunners that have gotten it down to a science). In addition, equipment later on in the game confers better stats than those picked up earlier and for the player to hit certain damage breakpoints they will want to equip them for the loadout that gives them the best stats. To further add to the puzzle, different party members have roles in battles dictated by their stats. For example, Surlent being in a Healer/Magic-User role, Legin being in a DPS/Crowd-Control role, Sork being in a Tank/DPS role and so their Elemental Affinities will dictate both their effectiveness at their roles and their survivability in a given battle. For Surlent whose MP pool is large and has a high Spirit stat, the player may setup their Elemental Affinity to favor survivability as he'll be the one responsible for healing the party and reviving downed members. For Legin whose HP pool is low and Speed stat is high, the player may setup their Element Affinity to favor the maximum amount of damage dealt (matching the Affinity of both their weapons and armor, countering that of the Enemies') as he will be constantly going up and down in a fight. For Sork whose HP pool is high, the player may setup their Element Affinity to be neutral as they can just soak attacks through sheer strength of stats. It may seem simple as I am laying it all out here, but the choices in-game feel meaningful and give the player a lot of agency to determine how best they wish to approach the next problem. On a design space basis, Element Affinity of armor is an engaging Rubik's cube in a game filled with many more systems to puzzle over. It must be said that the implications of Elemental Affinity apply across all three scenarios of the game, each of which has a completely different party, different areas (or at least different ordering of areas) and different Boss battles. The game is smart enough to not onboard the player with something so granular right away and slowly as they accrue new equipment let them figure out what they would require for the best combination. It also has some economy/inventory management implications as the player now has another layer to their choice of what Weapons and Armor to buy, who to give the old equipment to now that it has been freed up and what to sell back given that old equipment can still be useful at a later point in the game. Unfortunately, once the player reaches endgame (Day 16), a lot of these choices become simpler as endgame equipment clearly favors raw stats over the Element Affinity combinations. This can either be attributed to the limited development budget of the game or the fact that developers felt that as a minor system it didn't need as much in focus as other endgame content. Elemental Affinity of Armor is just one of the many systems that makes Treasure of the Rudras such a unique game to experience. Playing it now, more than two decades after its release, it feels like a game absolutely bursting with ideas that were never fully realized due to the niche it fell into. Treasure of the Rudras was a game released at the tail-end of the SNES generation, created on a limited budget as a standalone overshadowed by its bigger mainstream cousin Final Fantasy and until the fan translations never exposed to the world outside of Japan.

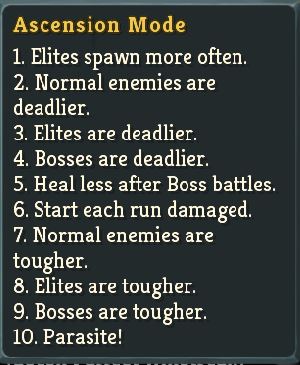

I hope that by deep-diving into a single system I could show you the level of thought put into the design of the game and perhaps encourage you to check out the game for yourself. It is a delightful mess of puzzly game systems, smooth sprite-based animation with trippy spell visuals, and sincere JRPG meditations on humanity and our place on the planet. Each of the three scenarios has their charms and it is satisfying to see them weave together to create a sprawling role-playing experience. The allusions to Hindu and Buddhist mythology in the game are not lost on me either having been raised in both traditions, further adding to its uniqueness in the JRPG canon. Treasure of the Rudras is still available to purchase in a variety of places. You can find the Aeon Genesis fanmade English translation here. The ROM is available on a few websites on the internet, however, until laws change you'll have to find it on your own (it's not hard). Design Gold is a series of short blogs reflecting on an effective element of game design in a game that I am currently playing and how it works to better the overall play experience. Blogs may be updated in the future as my understanding of how that element works changes. If you have known me for any amount of time, you know that I am a fiend for card games. I am particularly fond of collectible card games and deckbuilders as I find their design to be "crunchy" to uncover. Slay the Spire (2018, though technically still in Early Access) is one such game that has managed to hold my attention for over a month now. It is a roguelike deckbuilder where you play as one of three characters (The Ironclad, The Silent or The Defect) climbing a procedurally generated Spire filled with monsters, dangers and odd merchants. Each character starts with a deck of cards and can add new cards to their deck from a pool that is specific to their class. The goal of the game is to use your deck to defeat enemies and ultimately the Bosses of each Act in order to progress up the Spire. That core game loop in itself is pretty fascinating and there is a lot that can be said about the design of the encounters or the cards in each class pool, but for this blog I would like to focus on how the game encourages replayability and experimentation through a small and simple system: Ascension Levels. Before we get into that though, let me talk about the first time user experience of the game before you interact with Ascension Levels. When you first start the game, the player can only play as the Ironclad with a limited card pool. Playing through the first few runs, the player will slowly unlock sets of cards that will slowly expand the card pool and enable new types of decks. They will also slowly unlock the other classes, but not before hitting certain milestones first. This initial period of the game before the player beats Act 3 serves as a tutorial where the player learns how the game functions. For most people, this period will last within their first ~10 runs which is almost 6 - 8 hours in game. All of their efforts are being put towards getting that first Victory, which will be a combination of having memorized parts of the game and lucking into powerful cards and relics that synergize well. Once the player has beaten all 3 Acts with a single character, they will unlock Ascension Mode at Level 1 which adds a modifier to the base game making it slightly more challenging. It is completely optional for the player to engage in this Mode, so playing usually comes from an intrinsic motivation to want to get better at playing the game (but also supported by Achievement unlocks at completing Ascension Level 10 and 20). This simple inclusion will make a player's Slay the Spire play time go from 6 - 8 hours to easily 100 - 200 hours over the course of the next few weeks/months. Now, the goal is not about getting a single Victory, but instead about trying to win consistently no matter what elements of variance the game presents to you in a given run. By engaging in the climb to Ascension Level 20, players will have a chance to play a lot more of the game and thus see more combinations of the game's random elements. This will slowly help break the player's assumed first-order-optimal strategies and highlight new ways to build a deck for a given character. Players will also pay more attention to the map of each Act and thus navigate their way through the Spire with a better acknowledgement of the possible risks. At this point, the player will have unlocked most of their character's card pool and have seen a good number of Relics. This will allow them to make educated guesses about what synergetic elements they need to find and so players will naturally gravitate from tactical plays of their hand in a given turn to strategic plays of balancing resources in a given run. Achievements help in this regard to push players towards extremes of the deckbuilding system and get unique results like decks with 25 Focus, can make 999 Block, can play 25 cards in a turn etc. Players now become part of a new loop where for each Ascension Level, they will feel the incremental increase in challenge prevents them from getting a Victory and keep trying until they succeed to unlock the next Level. Now, difficulty levels have been done in a lot of different games (which will be discussed in detail at a later time) but here the steps are so gradual that it feels less like a power/skill curve wall and more like a hurdle that they can overcome ... if they just played one more run! And note, these are not just increases of challenge in scale (e.g. upping the numbers) but also in kind such as reducing the amount you heal after Boss battles or adding Curses (detrimental cards) to your starting deck. The changes of challenge in kind help highlight cards and Relics that the player might have otherwise passed over and enable strategies that they may have previously believed to be suboptimal or too "janky". The greatest benefit that Ascension Levels provide the players is how it subtly trains them over a long period of time to become more consistent with their play of the game. This period would usually be the "playing pubs" part of any competitive multiplayer game where the player must internalize good habits of play by being consistently defeated by better players. But this implementation feels a great deal better due to the fact that it is a single-player game and the difficulty modifiers are opt-in. Another consideration is that I believe the developers realize their audience will be primarily other card game players who have no doubt internalized a lot of half-truths about the nature of variance. Slay the Spire is surprisingly deterministic where it counts so that each Defeat can be traced back to misplays or deckbuilding faults of the player. The game provides excellent statistics and replay data which players can use to improve. Ascension Levels have done a lot to improve my enjoyment of the game and I will continue playing it until I hit Level 20. In order to create a little more replayability for myself, I have also restricted my play such that I need to clear a given Ascension Level on all three of my characters before I play the next one. And it has served me well! As of writing this blog, I have clocked in ~182 hours of playtime and have gotten up to Ascension Level 12.

I hope that my blog has highlighted what is effective about the design of Ascension Levels and I encourage everyone to give this game a try to experience for themselves what works about this system. Let me know your thoughts on this in the comments. Thanks for reading! Slay the Spire can be purchased on Steam Early Access here. Check out MegaCrit's (the creators) website here. I get this question occasionally and I'm interested in how my answer changes over time. But the core of the answer will always remain the same: to understand how people work. It might be odd that I didn't go into psychology or sociology or philosophy or economics or neurobiology instead, but I found that the magic circle games create around their players and how they chose to express themselves through its mechanics to be more revealing in the ways that I care about. I will admit that part of the motivation of this comes from a lack of common sense and social norms due to quite a sheltered and lonely childhood, so I am eager to make up the difference through my work. Games that I believe are successful designs are those that are able to create an engaging narrative arc (doesn't need to be a good story, but could be the progression of a player's own abilities), have a wide possibility space derive from a simple player actions, and have thematic cohesion in every aspect of its construction (from sound design to the choice of menu font). These are probably things that you have heard before from much smarter people or perhaps you might disagree with them, in which case make your case in the comments. There are three folks that I look to when thinking about design: Yasumi Matsuno, Mark Rosewater and Supergiant Games.  Yasumi Matsuno (YazMat) is a Japanese game designer and writer on titles such as Ogre Battle, Final Fantasy Tactics, Vagrant Story and Crimson Shroud. I came to know his work through one of the first games I owned and still go back to time and time again: Final Fantasy Tactics Advance. It was my first introduction to the world of Ivalice which remains one of the most detailed and wondrous that I have encountered in games. In my opinion, he is a master of low fantasy plots with large casts of characters and political intrigue. The English localization (done often by translator Alexander O. Smith) of his games have often taken a Shakespearean tone that elevates the work to an almost mythic level. The game designs are heavily systems oriented making them have a large learning curve at the beginning, but around mid-game players will understand enough to experiment and make their own ways of playing the game. My big takeaway from his work was to not compromise on one's vision (many feel Final Fantasy XII was full of missed opportunities) and build one's audience by commitment to aesthetic. YazMat's games a treasured rarity in any game library.  Mark Rosewater is an American game designer who has worked on the card game Magic: The Gathering for over 20 years. Rosewater is best known for making the game accessible to new audiences by adapting psychographics (Timmy, Johnny, and Spike) and narrative with story arcs and characters (such as the Planeswalkers) into its creative design. He is also an avid blogger and podcaster which has helped the community understand a lot of the decisions that go into Magic's design. I also highly recommend checking out his GDC talk: 20 Years 20 Lessons. Rosewater emphasizes his studies as a Communications major as being a critical part of his design process. One of his design pillars is the concept of lenticular design that any given element of your game should have an easily understandable use for new players and then as they gain experience that element is re-contextualized to have higher skill function. He is not a figure without controversy as many pro-players in the Magic community have railed against his initiatives (New World Order being a prominent example), but he is also the first to admit when a mistake has been made and tries to give good reasons for the decisions he makes.  Finally, we have Supergiant Games who are an indie game development studio formed by Amir Rao and Gavin Simon in 2009. Playing their first game Bastion was a massive turning point for me because that is when I realized that I wanted to pursue game design as a career. Bastion's brevity of language and purposefulness in every aspect of their design made it stand out from its competitors. There are many indie games can flaunt beautiful visuals, great music and robust mechanics but few can pull them together into a cohesive thematic whole that is a memorable experience in the way Supergiant does. Their second game Transistor shows their amazing toolbox design of interchangeable parts while their most recent game Pyre is a triumph of worldbuilding, character writing and incorporating loops of victory and defeat seamlessly into the narrative. They represent the high bar of game making that I constantly aspire to and I hope to work for them someday, even in a limited capacity. Hope that gives you all a better idea of what I am looking for in my designs. Whenever I'm in doubt, I ask myself what these folks would do. Sometimes I get different answers and that's fine because game design is a tricky thing where we must discover the answers by getting feedback from players and breaking through our own assumptions.

... have to come from somewhere, right? Here's hoping that my website is one of them!

So, why did I start a blog? I was hoping that it help me form some new habits and foster that fabled discipline I keep hearing about. A thing I have learned from being a netizen in 2018 is that a good way to foster engagement and retention is through inertia of content. What I mean by this is the phenomenon where you come upon some media you like and when you go to see what else the creator has done you find a lot more waiting for you. And so you go down the rabbit hole for the next few hours learning about every facet of this person's ouevre. This is an incredible rush to have ... until you catch up with all their content and now must wait with all of the others for the next time the creator graces us with their work. But if the body of work is large enough, it could take quite some time and that feeling of perpetual discovery can last. I want to use the blog in this way such that folks coming to check out my Portfolio or Media can gain a little insight about me and maybe stay for the sweet, sweet content. I also want to be able to look back at this post and feel physical pain at how poorly I started all this which would be a sign of how much I have grown since. And if at that time this website hasn't panned out or my fortunes have taken a turn for the worse, this will be the final post my future self shall read. And so, this good thing will finally have come to an end. |

AuthorSwarnava Banerjee is a game designer and programmer. Views expressed in these blogs are his own. Archives

October 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed